Waving a big hello to everyone! Cynthia has invited me to visit, and I’m always thrilled to be here. As many of you know, I love to write history in a story form. And what’s a story without a wonderful hero and a heroine worthy of him? Being I’m a totally hopeless romantic, how could I not write a story with love tangled into it? Writing about the frontier days of the American West is a time in history that appeals to men and women. But since we’ve never figured out how to travel backwards in time, a book will transport us there. My job is to make certain your experience is as real as possible.

My research turns up information that was never taught in schools. Often I wind up spending hours on information that I will never use, and I’m fascinated by all of it. When I started down this path of historical westerns, I had to research everything. I like knowing that what I’ve written is historically correct.

I’ve always admired and enjoyed reading another author, a European history professor Roberta Gellis. She wrote historical novels of old Europe and England. One of the things I liked about her books was the history that she put in the stories. Not just the clothing, but how the people actually lived, paid their taxes, and how those taxes were recorded on sticks. My feeling was why didn’t they teach us this stuff in school? I learned more reading her books than I ever did in a classroom. She showed me that history doesn’t have to be boring.

When I started working on my first historical story, I wanted to bring the same sort of accuracy to my work. Unfortunately, I didn’t have Ms. Gellis’ learned background. I began to research, checking, and double-checking resources. Often I chased my tail, and that can be frustrating. There’s plenty of misinformation, and it’s perpetuated in other places.

I thought the railroad went from point A to point C. No such luck! That section of track between points B and C should have been built by then, but it wasn’t completed for another twenty years. That’s a serious amount of time when writing a story. Yet that completed track between points B and C appears on more than a dozen maps! It was a railroad company historian, who gave me the correct information. I had to toss about 10 pages from a novel I was writing, rewrite those pages, and fix several other pages.

I thought the railroad went from point A to point C. No such luck! That section of track between points B and C should have been built by then, but it wasn’t completed for another twenty years. That’s a serious amount of time when writing a story. Yet that completed track between points B and C appears on more than a dozen maps! It was a railroad company historian, who gave me the correct information. I had to toss about 10 pages from a novel I was writing, rewrite those pages, and fix several other pages.

I’ve also had to make some strange decisions, especially when it comes to word choices. There were three very distinct divisions in spoken English. The educated people spoke a very formal form of English. Many recent immigrants tended to speak a broken form of English that also bled over to their children. And then there were those who spoke a regional dialect that almost sounds like gibberish to those unfamiliar with it. As a result, if I wrote exactly as each person spoke, it would make reading very difficult, so I tend to not be as stringent with keeping everything historically correct when it comes to speech. I do use dialects occasionally because it adds flavor, immediately identifies a character, and helps with the setting. I believe that the reader needs to be comfortable reading, therefore I keep such things to a minimum.

Nothing is worse than being yanked from a story over words that you don’t understand or an odd sentence structure. Our language is a mix of several languages and has settled into some speech patterns that we never think about until we study a foreign one. That’s when we discover that our yellow bus is bus yellow in another language because they place the adjectives behind the noun instead of in front of it. If I wrote the way a certain character spoke, it would become a difficult read. But wait, I do that occasionally. Then I read it a million times to be certain that the character’s spoken words are easily understood. A little can go a long way, but constantly deciphering sentences can be distracting. A Rancher’s Woman is sprinkled with such speech patterns, as is A Rancher’s Dream, but most people comprehend the German word Ja and Spanish word Si for our word yes.

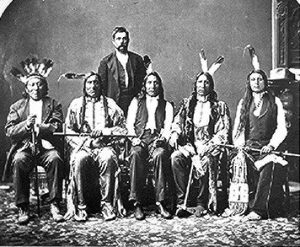

The other odd situation arises when attempting to write spoken words by our native tribe members. I haven’t looked closely at all the tribes, but the ones that I am using in my stories often struggled with our English language. It’s a fine line because I don’t want to portray them as being less intelligent. They weren’t. They lived, worked, played, hunted, married, and raised their children within their community. If they stepped outside that community, they were faced with people who spoke a different language.

Some did learn our language and very quickly! But to expect all of them to know and be fluent in our language is as ludicrous as saying everyone who lives in the states that border our Latino neighbors must know Spanish. Depending on the amount of contact with those people, they might or might not. There are also those who might understand what someone is saying, but can’t respond beyond a few words.

And remember when I said there are patterns in our language? We automatically use the past, future, and present tense, but what if there is no past, future, or present tense? It’s implied, depending on the situation. Such is the case with our many tribal languages. Anyone who has studied our American Sign Language instantly discovers that it, too, lacks those tenses.

And remember when I said there are patterns in our language? We automatically use the past, future, and present tense, but what if there is no past, future, or present tense? It’s implied, depending on the situation. Such is the case with our many tribal languages. Anyone who has studied our American Sign Language instantly discovers that it, too, lacks those tenses.

The more contact between people, the more each learns. So an American Indian might have virtually no knowledge of English until his or her contact is continuous. In my fictional town of Creed’s Crossing, Wyoming, there are several instances where families are fluent in Crow or Lakota and the English language. But learning a new language can be a struggle for adults, yet amazingly children learn so quickly.

In the beginning of A Rancher’s Woman, the hero Many Feathers, barely speaks our language. But it doesn’t take him long to learn because he’s completely surrounded with English speaking people, and he wants to learn. By the end of that story, he’s fluent in English and can read and write it.

Rose who is also a Crow, had no command of English, nor any need to be trained. Then Malene, the heroine, came to visit. The only thing the women had in common was the fact that they were women and understood cooking, cleaning, and babies. I’m certain it didn’t take them long to learn each other’s language once Malene remained on the reservation. The bonds of friendship would encourage the need to converse.

That situation is still true today. My husband’s family spent a little over two years in Naples, Italy, when the US Navy stationed my father-in-law there. My husband, as a teen, came home fluent in Italian. His father never spoke a word of it because he was constantly with other Americans on base, and they lived in a military community. My mother-in-law did slightly better because she had grown up in a French Canadian family and spoke French, therefore she often understood the Italians, but again her contact was limited mostly to shopping in the area, and what she did learn pertained to food names, ingredients, and cooking. But my husband embraced the opportunity to be in a foreign country and learn another language. Outgoing, fun loving, and quick to make friends, he mixed with the local young people. Since he spoke French, he had no problem learning another romance language. By the time he returned home, he was fluent.

Our native people were not stupid even though they often were portrayed as such in old TV shows or movies. They didn’t wander around grunting words like ugg. And anyone who has ever been around a man with a wrench on a rusted lug nut has heard plenty of uggs, grunts, and quite often more colorful words. So it’s easy to see how these people were portrayed when they did hard manual labor. But what we fail to realize is that many of them not only spoke their language, but the languages of neighboring tribes, French because of the number of French trappers that dealt with the tribes for years before the English began to settle there, and then some English because they were placed on reservations and had to cope with English speaking agents who knew no other language and many times had no desire to learn.

Our native people were not stupid even though they often were portrayed as such in old TV shows or movies. They didn’t wander around grunting words like ugg. And anyone who has ever been around a man with a wrench on a rusted lug nut has heard plenty of uggs, grunts, and quite often more colorful words. So it’s easy to see how these people were portrayed when they did hard manual labor. But what we fail to realize is that many of them not only spoke their language, but the languages of neighboring tribes, French because of the number of French trappers that dealt with the tribes for years before the English began to settle there, and then some English because they were placed on reservations and had to cope with English speaking agents who knew no other language and many times had no desire to learn.

Portraying our tribal, or any group of people, accurately and keeping the reader flowing through the story becomes a balancing act for the author and sometimes an editor. Many authors avoid the problem completely by pretending these people did not exist, or by showing them as completely fluent in English. Add one more piece into the puzzle – keeping things politically correct according to today’s standards. Huh? Not in what I write! I refuse to whitewash the truth.

Sometimes I get to giggling over reviews where my readers say my language is so clean, meaning no foul words, but it’s not unusual for my characters to curse. The difference is today we think nothing of the word darn, but in the late 1800’s, darn was not a polite word and tarnation was even worse! Although it was not on a par with the worst of the curse words today, it was still shocking. (One of the worst and most blasphemous was Dad!) And that brings up the question about some of today’s vulgar language. Did those words exist back then? Yes, but they were not in general use. There are several words today that are considered quite vulgar. But in the late 1800’s, they weren’t. If they were used, it was in normal conversation, and had to do with cattle breeding. It’s an interesting study. But foul words have almost always existed throughout time. And the curse words a man might utter back then when things went awry don’t raise an eyebrow today. That makes reading some novels rather funny when they use today’s curse words.

I will do my best to show things as they were and not as we’d like to think they were. I refuse to ignore the truth. I walk a thin line while writing. The desire to keep everything accurate, while allowing for comfortable reading, makes writing dialog a little challenging.

Today’s foul words were never used then as intensifiers. But I wonder what words will be tomorrow’s foul ones? What’s your favorite word when things go wrong?